A new feature of the Waves Conference program this year, “POPULAR MUSIC, EQUITY, DIVERSITY: The Struggle for Creative Justice” was created and hosted by Rosa Reitsamer and Rainer Prokop from the the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (MdW) and offered a broad and in-depth journey into topics of, as the title suggests, equity (and, of course, inequity) and diversity (or lack thereof) in popular music (in the broader sense of the word), on a national and international scale. The event went four hours long (4.5 as the program was much too interesting and engaging to be stopped, punctually).

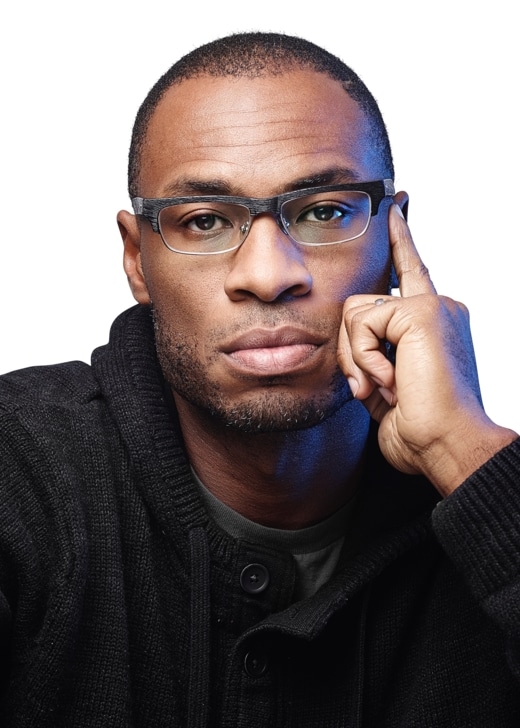

First up was a keynote presentation by MARK V. CAMPBELL with the title, in the form of a question: “Archiving Hip-Hop as Activism? Poetics and Possibilities”. Based in Canada, Mark V. Campbell is a DJ, scholar and curator who researches the relationships between Afrosonic innovations, hip-hop archives and notions of the human. He was invited to the conference to discuss his uniquely broad knowledge of hip-hop archives in Canada and North America, as well as globally. With it, he brought his personally critical perspective on what tenets the existing archives are built upon, and how they are maintained. In his view, they represent yet another facet of post-colonial practices and neoliberal abuses, or, at best, blind spots.

Campbell’s discussion ranged from hip-hop archives to exhibitions to auctions; the latter being notably problematic, with the inherent question of: who then owns the memorabilia of our culture? Essentially, who holds it hostage, how and why? As opposed to conventional forms of (hip-hop) archives, Campbell advocates for another form of archive: a living, breathing one imbued with joy; one which not only includes objects of the dead, but which celebrates and honors those who are alive today. Moreover, Campbell went into length about how he understands the value of an essential part of hip-hop culture: the Remix. As he put it, it is a method of producing new ideas from old ones, taking pre-recorded music and remixing it anew and, not least, it’s a way of thinking outside of Eurocentric perspectives. This is, of course, challenging mainstream society – a task that Mark V. Campbell seems to have made, in part, his life work.

The next point on the program was a performative presentation given by JAMIKA AJALON – an interdisciplinary artist and author whose recent debut novel “Skye Papers” (2021, Feminist Press) has won critical review (New York Times / Kirkus Review), and whose poetry and lyrics have manifested in more than a dozen albums, including the newly released “Rebooted” (Jamika & the Argonauts 2022). At the Waves Conference, Ajalon had an hour on the mic, in combination with visuals on the screen behind her, to bring forward the piece she calls: “Fugitive Diaries”. With her performance of spoken word, poetry and rock-hip-hop, she both captivated the audience, as well as disoriented it, with her non-linear storytelling and artistic expression, crossing realms of academia, history, her lived experiences, cultural insights, and socio-political commentary and references. Essentially, she created and presented a collage: one of music, song, language, emotions and histories, with, for example, video snippets of James Baldwin sprinkled throughout.

After Ajalon’s artistic whirl, she then turned to face the audience to answer questions; and of course, there were plenty. She explained, her novel, “Skye Papers”, from which she partially read, is centered around a female “On the Road” (1957) Jack Kerouac-like character, but with the added layer that the reader knows she is being watched; though it’s unbeknownst, who or why. As Ajalon explains, this speaks to surveillance issues as it relates to counter- and trans-Atlantic culture. When asked why Baldwin appears throughout her work, she explains that she draws a line between herself and him, being an Ex-Pat, herself, in France. Overall, the work – her performance, her writings, music and films – represent some form of Black female power as a symbol of resistance. Ajalon is the living embodiment of complex, non-linear resistance. And her art gives us a glimmer of insight into the universe that she has created from and within that.

The final point on the agenda of the MdW’s “POPULAR MUSIC, EQUITY, DIVERSITY” program was a Round Table Discussion, which was made up of some of the most interesting and influential figures in the Austrian music scene. Moderated by RAINER PROKOP (University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna/AT) and ROSA REITSAMER (University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna/AT), the Round Table was comprised of KEM KOLLERITSCH (Artist/AT), ESRA ÖZMEN (Artist/AT), WOLFGANG SCHLÖGL (Artist/AT), SHILLA STRELKA (Curator/Concert & Festival Organizer/Journalist/AT) and GERALD WENSCHITZ (DJ, Producer, Party Organizer /AT).

As expected, the discussion was a riveting one, which dove head first into some of the most potent and controversial issues that affect and permeate the Austrian pop, house and alternative scenes. The topics raised were many, and the discussions, very colorful, often heated. But a few threads that could be traced throughout were: how to create safer spaces for both fun and rage, through various strategies; specifically, community building and curatorial practices. Who the panelists are trying to reach and address through their music – why and how. What “diversity” really means at this point in 2022. And finally, questions of visibility and perception.

To the latter – questions of visibility and how it occurs, Esra Özmen (of EsRAP) explained that her position as a female rapper is what raised the awareness and attention around her music, which, at this point in her career, actually poses a struggle for her. That is, how to remove the brand of female rapper and just be seen as rapper. As she explains, although she is a feminist and much of her work is political, specifically around the issues of migration, she struggles at times to just be seen and heard as an artist, without all of the attached projections. As a female rapper, with Turkish, migrant roots, she feels her work is unnecessarily inspected and analyzed for political meaning, when in fact sometimes she just creates things for no reason, but the art itself – a luxury that many on the panel agreed is reserved for white CIS men, where they are usually not constantly questioned what the meaning is of everything they do, but can just create. Full stop.

Kem Kolleritsch (aka Kerosin95) agreed. No matter what work they do, it is and will be politicized, and they don’t have a choice in the matter. As Kolleritsch puts it, all they are seen through is the scope of gender. At this point, when doing interviews about gender issues (which they are completely tired of), Kolleritsch puts a price tag on them, and has also created the condition that only trans or queer people may conduct the interviews, as white CIS people tend to ask the most basic and uninteresting questions; as they call them: “Google questions”. To the question of who they address with their music, Kolleritsch answers: “Anyone who is up for the topics, and whoever is up for party and rage”. Also, specifically they want create a space for trans, queer and FLINTA people, where they “can all just chill for a sec”.

Gerald Wenschitz aka Gerald VDH adds to that. His audience is mainly “MSM” (men who have sex with men), a term he admits he actually hates. Nevertheless, he says they are “a very inclusive space, but not for everyone”. When it comes to the type of music he propagates, he says “I didn’t choose it (techno), it chose me. This music does what it does for a party, and party-music makes it easy to connect. […] It has a lot of rage – as gay people have, for obvious reasons. And this is why I choose these sounds at my parties. I think the music is crucial. It’s physical, it’s rough, it’s sexual, it’s angry.”

Wolfgang Schlögl explains that he is not building a scene at the moment (though he greatly respects those who do). He used to be part of a scene – the downtempo one of the 90’s. And back then, although there was some discussion and discourse around, the terms weren’t available then. And he believes, the more terms there are to discuss, the more communication there is about them. So, he is very glad that there is more discourse, and even more “rage” now, however, at the same time, he hopes the main aim is still to create an open society built on principles of humanism. And in that sense, he always tries to create an audience with that understanding, no matter the setting or medium. It’s all about the circumstances and on which principles you work.

Schlögl went on to impart his opinion to us on the music industry, as it currently stands: broken. “[…] it doesn’t really serve the musician. It serves the merchants.” He says, he has his ideals, and then there are realities, forcing him into certain structures which mostly leads to making compromises, “which makes me very uneasy. And that makes me think about stopping being a musician. Rather being a trainer for martial arts, for example. Because sometimes I feel that his has more social impact than being a musician.”

When Shilla Strelka (Struma+Iodine, Unsafe & Sounds) is asked about her process of curation, she responds that it’s very simple: she is trying to find people who are listening to the music that she can offer them. She is surely also always looking for a community, but one that is not exclusive. The kind of music that she is interested in, naturally has its place in the realm of politics – because sounds, aesthetics and the political belong together for her. These kinds of experimental sounds are always somehow tied to counter-culture. They are causing a kind of friction, a rupture, and they break with the dominant order, offering some kind of alternative to commercial music. She does not have a mission when it comes to booking, in terms of quotas or who she represents. First and foremost it’s about the sound. Because the sound is telling so much about world-views and open-mindedness. And this attracts certain audiences.

Schlögl, on the topic of inclusiveness: for him it’s about making music that is based on values of humanism – not driven by profit, capitalism, views or clicks – but based on the values of tolerance and making marginalized groups, visible. As a traveling musician, you may meet people from another part of the world. And he tries to work with them, eye to eye. Sometimes he succeeds, sometimes he doesn’t. He sees this as an inclusive way of making music. “Not for an elite European world view.” He admits it’s an idealistic view, “but maybe this is a bridge. Is this post-colonial or inclusive?” When he makes music in this way, he gets trolled for it. “It’s something you have to face, it’s ok. And sometimes it works, sometimes not. I’m not perfect.”

Rosa Reitsamer interjects, “I think the big challenge for white people is to unlearn privileges. […] you know, when you start from behind, it’s harder to push back. And white CIS men start from the very front. It’s easier for them to push back.” Wolfgang Schlögl whole-heartedly agrees and thanks her for this very important commentary.

Regarding structural questions, Özem says that the only way for an organization to be “diverse” is to have diverse people behind the scenes, working within the structure of the organization itself. And then there is the question of what diversity means, and how different that is to everyone. Where for one, it might be about the portion of females involved, for her, the number one factor is to do with migrant backgrounds. She sees a lot of challenges, and doesn’t see things really get better. She observers that the curators and organizers still don’t look at where they are offering what they are offering. She suggests, when you want to make a concert in a certain neighborhood or district, then first look at the existing place. Find out what the people are into there. Don’t just plop art and culture into a space that has nothing to do with it. Sound advice.

For Kollertisch, even the word “diverse” is problematic, as it is just thrown around lately, but the meaning is not clear; and not intersectional enough. For them, “It starts with people thinking about their hostility and privileges.” They put forward that curators really need to ask themselves: how are festivals and such genuinely made better by the inclusion of a diverse team and lineup? And not just because they need to check some boxes, and add “tokens” to their program. “A lot of people tokenize and accessorize people for the purpose of making their festival look really shiny. But the structures are still toxic and disgusting. And at the end of the day I am mostly performing at festivals where I am the only trans, queer or FLINTA person backstage. A lot of dudes backstage are topless. There are mostly only white people. Also a lot of queer festivals in Vienna are mostly white and able-bodied.” So although some people think they are being progressive, “in fact, there is a long way to go, deeper in that conversation.” And unfortunately rather the opposite happens, “and it stops. And I think that’s a huge problem. Because if you want to go further, then you have to deal with your own hostility and privileges. And that is a way that nobody wants to go; the uncomfortable way. I’m calling myself out. I’m calling artists out, curators out, myself included.”

Arianna Alfreds